By Matthew Johnson

We invited one of our latest staff members, Matthew Johnson, to share a bit about his background and his work at the NNCTC.

Rooted in Identity and Purpose

I’m Blackfeet, born and raised on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana—that’s my cultural identity. I come from a family of educators and have always been passionate about education. I started a TRIO program called Talent Search after a short stint in law school that ended when Congress cut my fellowship. I liked working with kids and eventually pursued a counseling credential. For 20 years, I was a counselor and teacher. I taught social-emotional learning (SEL), character education, and career exploration.

When I went to college, I learned to be an educator in the Western tradition. But two or three years into my job, I realized I didn’t like it anymore. The way I had been taught to teach created a power imbalance that emphasized control and compliance over relationships and inspiration. This was deeply troubling to me. Students didn’t like seeing me, and I didn’t like seeing them. This was around 2000 or 2001, before I had even heard the term trauma-informed.

I remember telling my wife, “I can’t do this anymore. I can't go to work and yell at kids. I can't keep writing referrals. I’m not enjoying it.” So I shifted my focus to building relationships with students—putting that first and truly getting to know them. In doing so, I stumbled into trauma-informed work without realizing it.

I noticed that on the rez, we had “haves” and “have-nots.” There were kids who were doing well—those with supportive parents and low ACE scores—and schools tended to revolve around them. Meanwhile, at-risk kids were denied access to many resources. We told ourselves it was because they were "bad," but I don’t believe any kid is bad. They’ve had bad experiences, they carry trauma, and they lack certain skills and supports. I focused on helping those kids find growth-focused solutions instead of punitive ones. Kids began enjoying coming to my office, and I started liking my job again.

In 2007, Dr. Marilyn Zimmerman came to the school for a professional development session. Only 10 or 12 out of 60 staff attended, but it was impactful. It opened my eyes and affirmed that I was on the right path. It gave me a foundation and made me feel supported in my goals. Schools should not retraumatize students—they can be healing places.

The Buffalo Hide Academy: Returning to Traditional Ways of Learning

A couple of years later, the school superintendent asked me to take over alternative education. We had the autonomy to build the best alternative school we could. We called it Buffalo Hide Academy. We made a conscious decision not to create a Westernized school. Our ethos was: Let’s try to heal these kids first. Then we’ll teach them.

With help from counselor Charlie Spicer, we connected with Dr. Maegan Rides at the Door from the National Native Children's Trauma Center. She echoed Marilyn’s insights and reinvigorated us. We became trauma-informed all day, every day. We eliminated discipline referrals, in-school suspension, clip charts—even PBIS. We didn’t care if students called us Mr. or Mrs.—that’s Westernized. We didn’t have bells. Kids used their phones to move between classes, and our attendance and punctuality were better than traditional schools.

We asked ourselves: What did education look like 500 years ago? It didn’t look like bells and desks. It looked like learning at the buffalo jump—science, math, and history all rolled into one experience. That’s how we taught. We leaned into traditional ways. We used restorative practices and embraced our oral tradition—not just speaking, but listening: listening without correcting, without anger. People heal when they’re heard, and that value shaped how we engaged both staff and students.

The results were incredible. Profoundly at-risk kids—some with a dozen fights on their records—never fought in our school. We never had to call law enforcement. Instead of hiring a vice principal, we asked for another counselor. Visitors consistently told us our school was the calmest, most supportive place they’d ever seen.

We also wanted the school to reflect our students. That meant celebrating not just Blackfeet culture, but also the culture of adolescence—skateboarding, rap music, whatever they were into. Whether a student was transgender or had a different faith, we met them where they were. We created a school they loved coming to.

Leadership Through Trust and Culture

As the administrator, I had less one-on-one time with students, so my focus shifted to defining what trauma-informed leadership looked like. I wanted a school where employees loved coming to work, where they had autonomy and trust. I encouraged them to teach boldly and connect deeply with students. We wanted our school to feel like grandma’s house—where you’re fed, affirmed, and supported. Our approach was trauma-informed, restorative, and culturally integrated. People came from all over to see it. What we were doing was eventually written up and published in the Harvard Educational Review.

In addition to my career in education, I served as an appellate court judge for the Blackfeet Tribe for five years and taught history and literature at Blackfeet Community College (BCC) for 17 years. I’ll never leave the Blackfeet Rez. We’ve never been relocated—we’re in the same place we were 20,000 years ago. It gives us a deep sense of self. Maslow once visited the Blackfeet and misunderstood a lot. He was expecting hierarchy, but what we had was agency and autonomy. The Blackfeet word for our tribe, Kainai, means “many chiefs.” We simply existed and took care of each other.

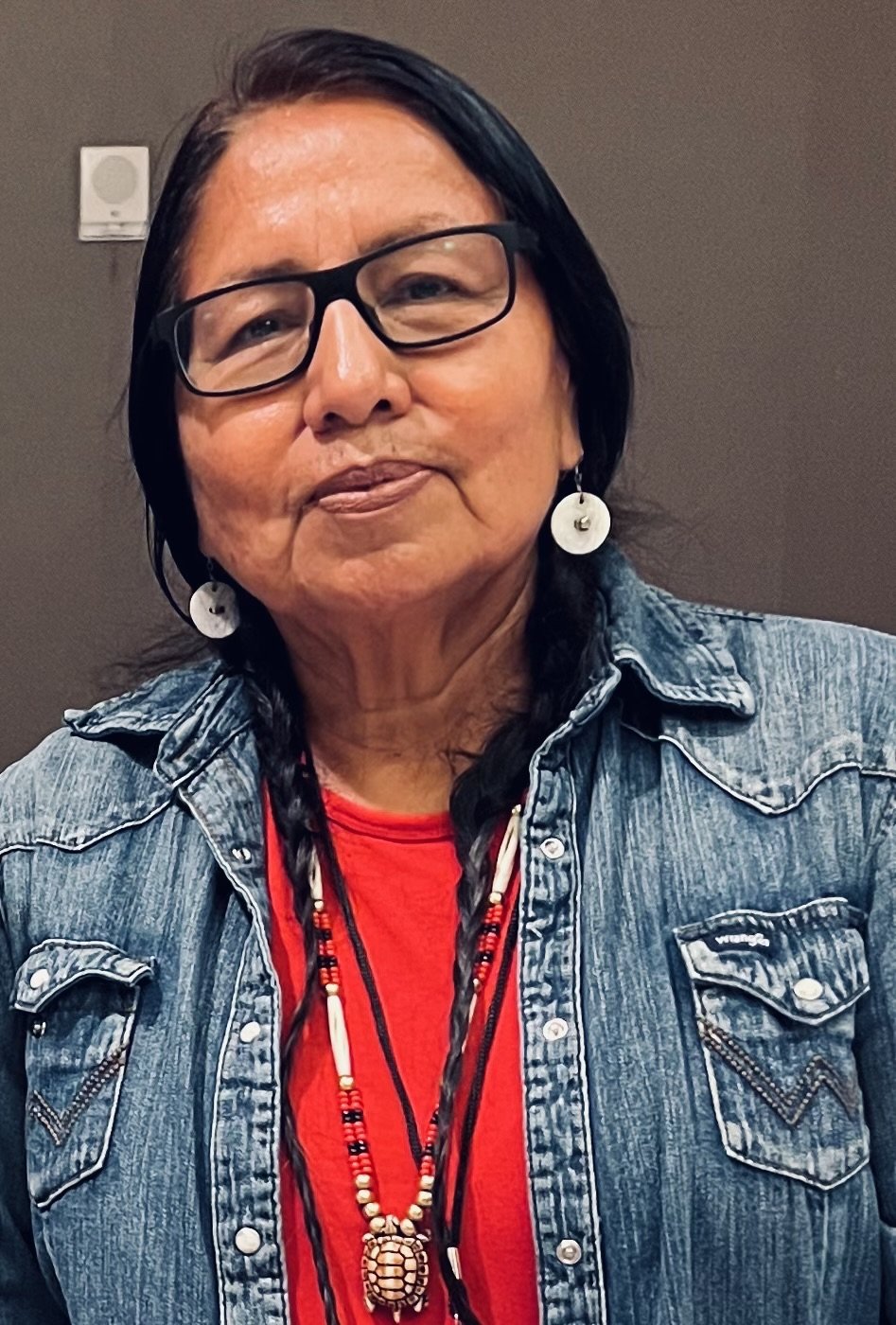

NNCTC Training and TA Specialist Matthew Johnson (bottom right) and his family.

Family, Healing, and New Chapters

Outside of work, I’m very family-oriented. I love cooking, family gatherings, and golf. I used to coach sports but stepped away. Sports can be powerful—for better or worse. Too many coaches yelled, belittled, and ignored struggling kids. But our athletes don’t want to be belittled—they want trust. That’s what we did at Buffalo Hide: gave kids a safe place where they could thrive.

On a personal level, I have a beautiful wife, who is also a Tribal member and an administrator at BCC. She also owns a small fabric store. I have two wonderful kids—one’s a college athlete, the other is a student at BCC.

I lost an adopted son to suicide last year. He had been abandoned, and I felt it was important that someone grieve him properly. I was his person. In our culture, we grieve for a year—no celebrations, no powwows, no holidays. After that year, we stop grieving and celebrate the person’s life.

After that loss, I stepped away from schools and took a job at the National Native Children’s Trauma Center (NNCTC). At NNCTC, I feel like I’m with people who genuinely care. After losing my son, I was struggling. I reached out, and everyone at NNCTC supported me. Maegan models leadership with compassion. That kind of trust and support is rare in Indian Country—but here, it’s real, and it’s powerful.