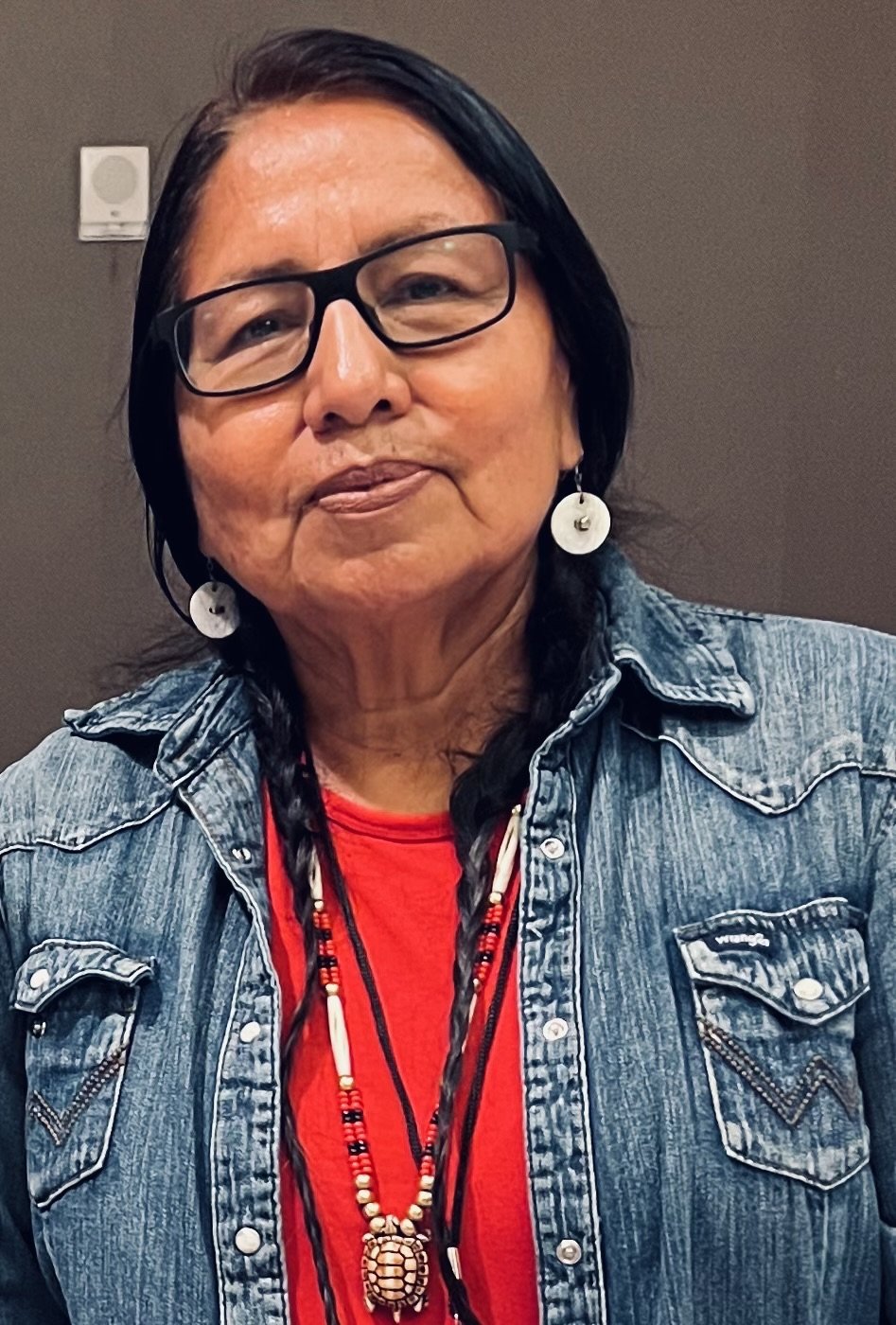

Ethleen Iron Cloud-Two Dogs (Oglala Lakota) and Shannon Crossbear (Ojibwe), Cultural Consultants for the NNCTC, draw on their knowledge of their own Tribal cultures to advise our Center and our partners on strength-based approaches to promoting resilience. We invited Ethleen and Shannon to share any reflections they might have on the occasion of Indigenous People’s Day (October 9, 2023) as it relates to our work at NNCTC.

Ethleen Iron Cloud-Two Dogs

Shannon Crossbear

Ethleen’s Reflection

When marking Indigenous People’s Day last year, President Biden said, “We honor the sovereignty, resilience, and immense contributions that Native Americans have made to the world; and we recommit to upholding our solemn trust and treaty responsibilities to Tribal Nations, strengthening our Nation-to-Nation ties.” These are important thoughts, and I am glad to hear them coming from the highest levels of the federal government. As we know, the government has not always spoken in this way about Indigenous people and Tribal Nations. Tragically, many of our relatives still carry the spirit burden of the trauma, grief, and loss from generations past, and the effects on the children and youth continue to be devastating.

Indigenous people everywhere acknowledge, appreciate, and honor their precious and beautiful cultural lifeways that have been sustained for thousands of years amidst horrendous histories of trauma. At NNCTC, our training and technical assistance approach is grounded in the belief that these lifeways are at the heart of resilience. Indigenous nations have the answers to how to heal those intergenerational wounds.

NNCTC seeks to engage with Indigenous people and nations as relatives, honoring the cultural and spiritual lifeways that were gifted by the Creator. I was pleased to see this conception of relatives expressed in the popular TV series Reservation Dogs, when one of the characters says, “I’m your grandson, even if I’m not.” I felt the same thing recently when visiting with some youth who were detained in a Tribal juvenile detention center. I told those young people, “I’m your grandmother, even if we’re not blood related. We still belong to each other. We’re human relatives.” Such sentiments—“We are all related”—are common among many Indigenous nations. This is a way of promoting and modeling healing: to treat one another as relatives. This goes for human relatives, four-legged relatives, winged relatives, and plant relatives. The healing energy that is produced compounds and becomes active in every interaction or encounter.

As we celebrate Indigenous People’s Day this autumn, I am also thinking about how people historically lived according to a seasonal and spiritual calendar. They knew when to do what because they were in tune with the universe and understood they needed to be a respectful relative who contributed to a healthy ecosystem so that all living entities could thrive in a healing environment. This makes me think of a discussion that my Ojibwe relative and colleague Shannon had recently about the importance of food sovereignty and, more specifically, how her culture includes respect for the water and the “food that grew upon the water”: wild rice. Let’s hear more from Shannon about that.

Shannon’s Reflection

It is dagwagin, autumn, in the lands of the Ojibwe peoples, and the gathering of the wild rice has just finished for the year. Now the bragging about the success of individuals’ or families’ harvests has begun, along with comparisons of flavors and types, short or long grain, dark or light. There is the selling and trading and eating. Feasting and eating!

In recent years we have heard more and more about food sovereignty and its importance to our Indigenous communities. When Europeans reached these shores, the reports were of healthy and robust peoples. There were many Western accounts describing the conditions of communities that were self-sustaining. So how is it that communities sustained by generations of hunting and gathering became the food deserts of the continent? How is it that we ended up with some of the highest percentages of diabetes and kidney failure? Between the devastation of food sources such as the buffalo and beaver and government policies meant to starve Indigenous nations into compliance, we found ourselves reliant on food sources such as those that were provided by the federal government. Even the precious corn of the southwest has been manipulated, controlled, altered, and commodified. In the process, it has become less healthy. Now, Tribe by Tribe, nation by nation, we must reclaim the sovereignty and health of our people.

Within a worldview that encompasses all things being related, we cannot separate our stories, our spirituality, our physicality, and our reliance on and relationship with our food sources. Food enables us to acquire and maintain what the Ojibwe peoples refer to as mino bimaadazawin: a good life path, wellness, and well-being. Whether it be the buffalo, the salmon, the squash, or the rice, we all have stories that describe how that food source fits into our cosmology.

Let us use the manoomin, wild rice, as an example. The stories about how the Ojibwe came to this part of the country are intertwined with wild rice. It is said that we originally came from the east and that this journey took place prior to European contact. We traveled in a large group and our destination was to be where the food grew upon the water. We were told the food source would sustain us through the harsh winters or when the game was in short supply. We were told to develop a relationship with the wild rice, to allow it to teach us. After generations we finally settled into what was to become our homelands. The place where the food grew upon the water. The Lake Superior Ojibwe were home.

We subsequently learned and honored the relationship with wild rice. Wild rice, in turn, provided, and continues to provide us, with healing and health. We learned how to harvest in a manner that was in alignment with natural law. We became the caretakers of the rice, and the rice cared for us. We have never wavered from that sacred responsibility, and today there are those who are fighting for rice. They understand that the health of rice reflects the health of the people.

It is an Indigenous value to care for our food sources. These teachings are incorporated into our very way of living. Preparing for the gathering of the rice. Getting the canoe ready. Scouting out the ripeness of the rice. Deciding where and when to rice. Preparing your thoughts and mind and heart to be with the rice. It is in these moments that generational knowledge is transferred. The knowledge about what to gather and what to leave behind for reseeding. Our physical being is cared for in the labor of carrying a canoe and using the knocking poles. It strengthens biceps and core. There is the dancing on the rice, the winnowing, and the processing that adds to our physical strength. “Ricing” requires more than one person, so it creates community connection.

It is in everyday actions that we can include cultural teachings and build upon ancestral wisdom. Recently, I was facilitating a small energizing exercise for a group. We played out some of the actions of ricing to stretch our bodies. I provided a few stories about the wild rice process and the Ojibwe. We had a chance to stretch our minds and learn something. When we got back to work, we did so with a renewed spirit.

How do we decolonize? Talking at the tables where we share food is wonderful. Especially if it is in our respective languages. Gathering the wild rice to serve at the table is even better. I will bring the rice, I will have my Lakota relatives bring the buffalo, my Dine’ relatives bring the corn, and we will round it out with some sweet maple from our relatives from grandmother country.

Indigenous Nations are honored on this day, October 9, 2023. However, we know that we have paid a heavy price for this accolade and that our battle for healing for our children, youth, families, and communities will rage on. At the same time, we revel in the fact that many Indigenous nations still have their language, their ceremonies, their custom, and most of all hopes and prayers that healing is possible. On this day, I would like to suggest that we take a “device detox” day, putting down our technology and taking part in a healing activity, whatever that may be, because we all deserve healing.

We invited our relatives on our NNCTC team to respond to the following prompt: What three words come to mind when you think about Indigenous Peoples, and Indigenous Peoples’ Day? We used those responses to create this word cloud.